Dearfield, Colorado

submitted by Dr. George H. Junne, Jr., UNC

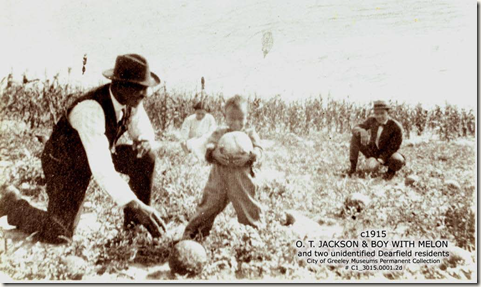

Colorado entrepreneur and messenger for three governors, Mr. O. T. (Oliver Toussaint) Jackson filed a desert claim to create the African-American agricultural colony of Dearfield in May 1910. Dr. Joseph H. P. Westbrook, a Denver physician, proclaimed at an organizational meeting in 1909 that the fields “will be very dear to us,” thus giving Dearfield its name.

The first settlers came in 1911, and by 1920, the successful community of Dearfield had a population of between 200 to 300 residents, two churches, a school and restaurant, plus plans to build a canning factory and a college. Dearfield’s dreams turned to dust in the 1930s Dust Bowl, and the town never recovered. By 1946, Dearfield had a population of 1. Today Dearfield remains a symbol of Western pride and empowerment for many African Americans.

THE STORY OF DEARFIELD COLORADO

(taken with permission from a presentation created by Robert Brunswig)

(taken with permission from a presentation created by Robert Brunswig)

“Get a home of your own. Get some property….get some of the substance for yourself.”

-- Booker T. Washington

Booker T. Washington’s advice, coinciding with an African-American “back to the land” movement at the turn of the 20th Century, inspired O.T. Jackson to invest his own money to buy land for a black colony located on Highway 34, ninety miles north of Denver.

Booker T. Washington’s advice, coinciding with an African-American “back to the land” movement at the turn of the 20th Century, inspired O.T. Jackson to invest his own money to buy land for a black colony located on Highway 34, ninety miles north of Denver.

Jackson established Dearfield as a self-sufficient all-black agricultural colony.

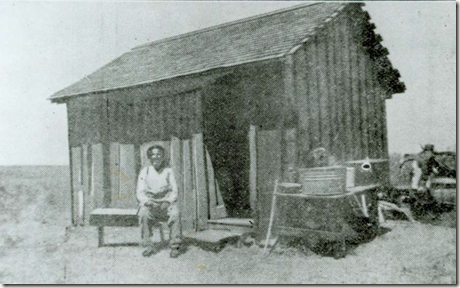

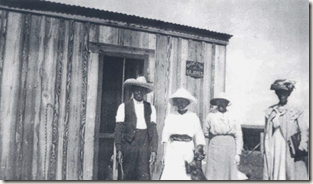

In 1910, Dearfield’s first seven homesteaders established land claims, initially living in tents and dugouts.

In 1910, Dearfield’s first seven homesteaders established land claims, initially living in tents and dugouts.

The colony’s first recruit was an elderly man and friend of Jackson, J.M. Thomas. On August 20th, 1910, James Smith and J.M. Thomas of Denver planted 100 acres of winter wheat.

In 1911, the first full year of settlement, seven families moved to Dearfield, surviving that year’s severe winter together in only two frame houses. By 1915, the town’s population had grown to include 27 families, 44 wood cabins, a concrete block factory, dance pavilion, lodge, restaurant, grocery store, and a boarding house.

In 1911, the first full year of settlement, seven families moved to Dearfield, surviving that year’s severe winter together in only two frame houses. By 1915, the town’s population had grown to include 27 families, 44 wood cabins, a concrete block factory, dance pavilion, lodge, restaurant, grocery store, and a boarding house.

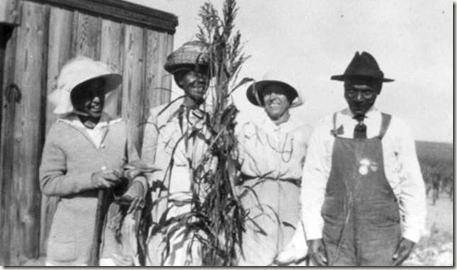

Settlers dry-farmed corn, oats, barley, alfalfa, hay, potatoes, Mexican beans, sugar beets, cantaloupes, strawberries, and a wide variety of truck garden products.

They also raised cattle, horses, hogs, turkeys, geese, ducks, and chickens.

Some farmers went beyond subsistence farming and grew crops for the Kuner’s factory, the Beatrice Creamery, and the Green Brothers Fruit and Produce Company in Denver.

In 1920, Dearfield farmers produced the colony’s largest crop, one third more than in the previous year.

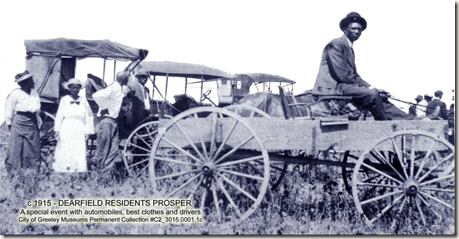

By 1921, sixty to seventy families lived in Dearfield. Its net worth that year was appraised at $1,075,000.

In 1921, fifteen thousand of the community’s 20,000 total farm acres were under cultivation and the growing town added two churches and a gas station.

Many Dearfield colonists came from Denver, others from as far away as Missouri, Texas, Arkansas, Georgia, Massachusetts, and Virginia.

Aside from farming, people worked in retail businesses and truck gardening. Hosting week-end dances for visitors from Denver were important social occasions and a source of revenue for Dearfield community members.

Many people from Denver’s African-American community would travel to Dearfield on those week-ends by car and by train, there being a train station only a mile and a half away at another nearby small community.

Advertisements of Dearfield’s entertainment offerings were placed throughout Denver’s Historic Five Points neighborhood and many of its residents traveled to Dearfield on weekends for great food, fun, and dances at its Barn Pavilion.

Many Dearfield residents worked in Denver during weekdays and farmed their homesteads on weekends.

This meant that much of the responsibility for farming fell on the men’s families during the week-days when they were employed in Denver.

Women and children ‘s contributions in vegetable gardening were a particularly significant source of both household food supplies and a source of outside income during the summer months.

Inflated food prices of World War I fell suddenly when the war ended and over 400,000 U.S. farmers lost their land.

In Dearfield, those who lived through the 1920s suffered economic downturns as their soil dried up and blew away in the hot, dry winds of the Dust Bowl.

Jackson’s dreams turned to dust as Dearfield and many other eastern Colorado farming communities suffered economic downturns beyond their control.

Dearfield residents drifted away to find better opportunities and, by 1940, the town’s population had decreased to twelve, only two percent of the town’s highest (1921) population.

O.T. Jackson desperately attempted to revive interest, even offering Dearfield for sale, but there were no takers.

Jackson lived on at Dearfield until his death on February 18th, 1948.

Today, little evidence remains of the tenacious individuals who brought life to Dearfield.

In 1995, Dearfield was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

In 1999, Colorado Preservation, Inc. (CPI) listed Dearfield as an endangered site.

The Preservation of Dearfield

The Black American West Museum, with other community and university partners, is actively working to preserve Dearfield’s heritage by stabilizing existing structures and documenting its past. An archaeological research program is planned, starting in 2011.

With care and support, Dearfield’s past can be preserved for future generations and, hopefully, may become a popular as well as an important learning experience for

Colorado school students about the state’s rich social and cultural heritage.

With stabilization of existing buildings and new research, future creation of a historic park and museum is envisioned in Dearfield’s future.

In 2002, the Black American West Museum joined Colorado Preservation Inc. and Colorado State University’s Architectural Preservation Institute in stabilizing Jackson’s home, and in 2004, the Black American West Museum acquired much of the original town site.

Saving Dearfield and Preserving its Heritage

Through efforts of the Black American West Museum, local governmental and non-profit organizations, and the University of Northern Colorado, all members of the Dearfield Historic Preservation Committee, reminders of that past can still be preserved. But the chance will not last long – the buildings are in immediate need. You can contribute to ensuring the future of this authentic piece of history.

Immediate needs for preserving Dearfield are for continued stabilization of surviving buildings and maintaining its property taxes. An adopt-a-lot patron investment program has been implemented. A monument at the site is already constructed and in place, dedicated at the Dearfield 100th anniversary on September 26th, 2010. Long-term plans and future funding initiatives for historical and archaeological studies of the site and its surviving historical records have already begun and archaeological field studies will start in 2011.

The Dearfield Research Project will be a partnered community engagement effort, involving participation of community members from Greeley and Weld County and Denver, volunteers and staff at the Black American West Museum in Denver, university faculty and students at the University of Northern Colorado, non-profit organizations such as Colorado Preservation, Inc., city and county governments and museums in northeastern Colorado, and students and teachers from schools in Weld County and Denver. Publications and school curriculum materials resulting from that research will be developed to enrich heritage education opportunities to the general public as well as Colorado’s K-12 and university students.

Black American West Museum

Dearfield Fund

3091 California Street

Denver, Colorado 80205

Phone: 303-482-2242

www.blackamericanwestmuseum.com